Dispatch 11: "The Lights Are Still On"

17th August 2012

I had a moment of awareness several years ago aboard R/V Knorr in the Agulhas Current, the Indian Ocean’s version of the Gulf Stream, when I sat at dinner across from the Chief Engineer, and asked him how his work was going. He replied, “Well, the lights are still on.” I had been blithely flicking on my cabin lights, taking a daily shower, sitting down to three hot meals a day, etc., with scant thought to just how these hotel-like amenities came to be, and abashedly admitted as much. “That’s good,” said the Chief. “It means everything is working.”

|

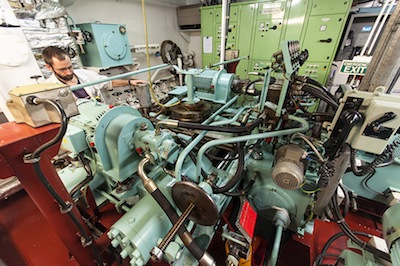

To keep everything working—the province of the engineering department—is not easy on any ship, but especially challenging on JCR in its combined role as a high-latitude research ship with ice-breaking capability (technically, she’s not an icebreaker, but “ice-strengthened). The other day Glynn, the Second Engineer, took Rachel and I on a generous tour of the engine rooms, which her photos will illustrate more accessibly than my description.

The nerve center for all ship systems, from which pressures and temperatures are monitored, power distributed throughout the ship, and machinery started or stopped. |

Air conditioning units for labs spaces. Other units air condition the public and living spaces. |

JCR’s engine rooms are fully automated, and so need not be manned at night. The engineers rotate “on-call” night duties, their cabins, mess room, and most public spaces are rigged with alarms in case something goes amiss below. The daily spheres of responsibility for each engineer have been long established by nautical tradition. Jim (locally known as Mango), as Third Engineer (3/E), is responsible for fuel injection equipment, air compressors, and the sewage plant. Steve, the 4/E, tends to the fuel oil, lube oil purifiers, fuel oil bunkering (loading), and internal oil transfers. Mark and Ian, the “motormen,” called “oilers” on American ships, keep the machinery rooms and the public spaces clean and assist the engineers as needed. Three other specialists report directly to Dave: Simon, the Deck Engineer, is in charge of all topside machinery, including the big cranes, so essential to JCR’s scientific work and as her duties as supply ship to remote British Antarctic Survey bases. Radio Officer Charlie and Nick, electro-technical Officer, are in charge, respectively, of the many, myriad electrical gear on the bridge, and the other electronics below the bridge.

Bow thruster shaft and steering motor. Bow thruster is powered by a 1,115 kW DC motor; the stern thruster (558 kW) is driven by hydraulics. |

Glynn, as 2/E, is the “working boss” of the department, responsible for assigning work, managing the engineering personnel and, specifically, for the refrigeration and air-conditioning plants. Typically, the 2/E would advance at some point to chief, but Glynn says he’s happy where he is. “I like to get my hands dirty,” as he put it during our tour. In his view the C/E’s job involves too much paperwork. “I have enough of that already.” Serving as the BAS supply ship, JCR carries everything you can think of from snowmobiles to 360 cubic meters of aviation fuel to coats and hats, food and toilet paper to Antarctica. It falls to Glynn to inventory all ship’s mechanical needs down to spanners, nuts, and bolts. (On this trip, people play soccer in one of her enormous, nearly empty holds.) She’s scheduled for an overdue dry-dock refit in Denmark next month, adding to the engineer’s workload.

Aft end of the “shaft tunnel.” The shaft connected directly to the propeller provides forward/astern propulsion. Blue unit is a main shaft bearing. The stern thruster is situated on the deck below. |

Propulsion

Electric propulsion motor and bearing at the forward end of the shaft. |

Motorman Ian enjoying his work in the incinerator room. All garbage is segregated and all burnables go into incinerator. Nothing goes overboard. Bottle and can crusher is at his left. |

Glynn inspecting the R32 Wartsila Vasa Diesel engine in the main alternator room. We see the rocker covers for the eight cylinders and partially exposed fuel pump “gallery.” If running simultaneously the four engines would produce 8,200 kW of electricity. |

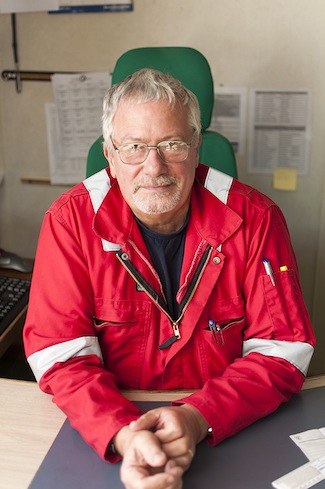

Chief Engineer Dave Cutting |

JCR in dry dock at Her Majesty’s Naval Base Portsmouth, 2008. (photo credit: Glynn Collard) |